The Boston Common is a layered and conflicted site. A symbol of the complex (and potentially unattainable) project of pursuing freedom for all.

There has never been an achieved or completed project of freedom for all, and there has never been a non-conflicted or non-contradictory (Boston) Common. An idea of common is inherently exclusionary and thus to be truthful must function as a perpetual site of unearthing and revealing the contradictions of what is in common and what is freedom.

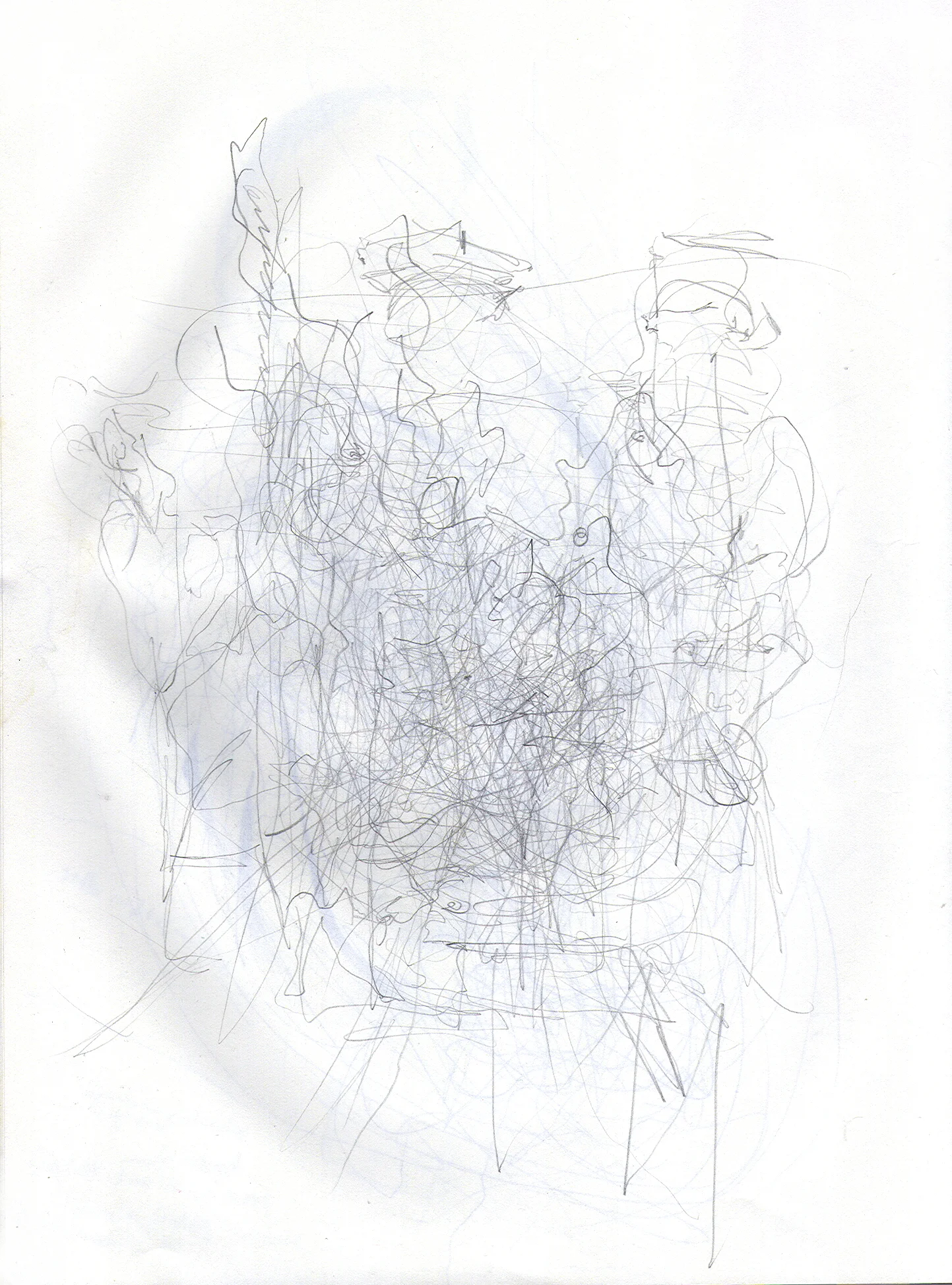

The Great Elm tree stood on the Boston Common for 250 years, growing to span over 100 feet in diameter. The tree was used for many years for public hangings, including the well known case of Mary Dyer who lost her life for being Quaker in the Puritan Colony. The tree was later glorified and personified publicly as Boston’s “oldest living inhabitant”, and as a “Beloved Citizen. Amongst current statues and monuments in the Common, the site where the Great Elm stood is now empty.

Why is the tree absent now?

What is an appropriate way to conjure its presence, or to respond in the site?

Under the title Beloved Citizen, we propose the installation of an Elm sapling, approximately 10 foot tall, on the site where the Great Elm stood. This sapling would be planted and then unplanted a year later to be replaced by another. This replacement would occur annually, integrating into its action a ritual in which the removed tree is given to an individual or group to take out of the site and plant elsewhere.

Our use of the title Beloved Citizen refers to two meanings; the right of all people to be beloved and to belong, and the existence of many experiences of rejection and being cast out unjustly, either through exile or loss of life. The word citizen has two definitions, legally recognized member of a nation state, or inhabitant of a region. We refer to the latter.

The bodies of people hung on the Great Elm, including those whose lives were taken unjustly, were buried in the Common in unmarked graves; their location within the site is unknown.

When a hole is dug for the elm sapling, their bodies are conjured and unearthed. When the tree grows, they are honored in their role of giving nutrient-life to the tree, which nurtures new sentiments and relation to history.

The careful steps required for transplanting a tree form the basis of a task based community ritual.

The root system of the tree must be measured, and the root ball gently excavated. The tree lifted and separated from the site, is then wrapped in burlap, tied, and placed in a container to protect and secure it for travel. A new young sapling is then planted in the same hole in the site, the burlap cut to release its roots, and soil carefully packed in around. When this tree has been settled and the tasks in the site are complete, the group will travel to the new site and repeat the process of planting together. The form of this processional will reflect the mindful collective quality of the unplanting, and will be designed annually in response to the distance and nature of the destination site.

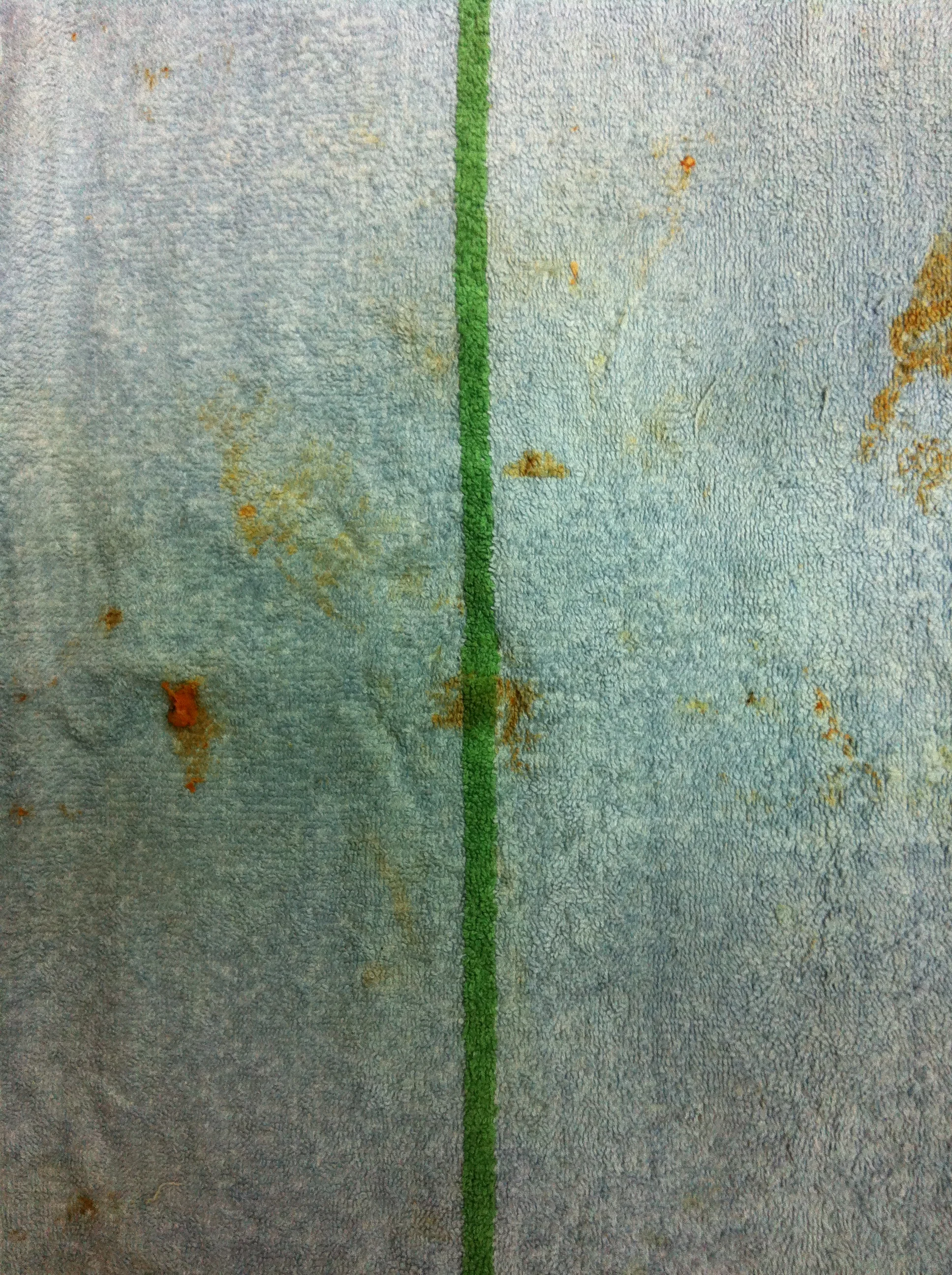

Each basic action in this process can be refined and transformed to deepen its meaning. The order and direction in which the burlap cloth is folded, moving counterclockwise, corner by corner. The string continuing this trajectory, as it travels from the neck to the base of each face of the root ball, slowly forming an intricate knotted pattern. Gathered people perform these actions together, each taking a role which is carried out in a mutual choreography.

Each year people in Massachusetts will be invited to submit letters and videos, sharing personal connection to the subject of the Beloved Citizen, in the context of discrimination, harm or displacement, and expressing interest in becoming caretaker and guardian of the sapling. We will actively reach out to classrooms, activists and community organizations to build awareness of the project and invite submissions. These voices form a new public layer of the project, a continuous rearticulation of the relationship between the historic site and contemporary experience. These documents will be permanently housed on a website, along with an image map showing the location of a growing collection of saplings transplanted outside the Common. One name will be drawn each year to determine the group or individual who will receive guardianship of the tree.

By uprooting the tree, we are not denying the reality of harm, but acknowledging and enacting it through the stress and risk that the process generates in the body of the tree. Vulnerability and responsibility are palpable when performing the transplant process, and become a point of contemplation. The distinction lies in the intention and care that are cultivated by collectively carrying out the necessary steps, task becoming social engagement and transformative process.

The project breaks the sanctity of dominant historical ground which has been established in the Common. Staking a new relation to history in the site, revealing freedom and democracy as inherently problematic, and continuously forming. Digging transgresses power and control boundaries of the public site of the common. The site can thus function symbolically and actually to nurture inquiries which unearth present injustices and acknowledge those who have suffered.

Sujin Lim & Kathryn Abarbanel